PsychoanalysisLacan is the free, online journal of the Lacan Circle of Australia

We publish contemporary psychoanalysis in the Lacanian orientation

Volume 5: Lockdown!

Jonathan Redmond

The editorial committee at PsychoanalysisLacan is thrilled to release its new journal – Lockdown! – as part of the Lacan Circle of Australia’s annual publication. Living through lockdowns has been one of the common experiences for humanity during the pandemic – most of us have had some experience with being stuck in our homes or have had restrictions of work and travel. In Australia, the city of Melbourne has the inauspicious record of being in lockdown for longer than any other city in the world with six lockdowns totalling 262 days since March 2020. And while Australia’s penchant for lockdowns and border closures is uncannily appropriate for the once British penal colony the disorder and upheaval this has produced for speaking bodies both in Australia and across the world has been significant. And with the global pandemic showing no signs of abating as the new Omicron variant currently sweeps the globe the veritable truth conveyed in the statement “The show must go on” – often in virtual form – has ushered in new modes of working for many of us in the in the New Lacanian School (NLS) and across the World Association of Psychoanalysis (WAP).

At the Lacan Circle the show has indeed gone on – the dark days of the global pandemic have coincided with new forms of engagement in analytic discourse with thousands of online users from around the world plugging into theoretical seminars, author interviews, cartels, reading groups and clinical seminars. This journal bears the fruit of the labour evident in the LCA of the pandemic. The LCA, as an affiliate member of the NLS aims to publish both Australian and international authors to showcase the broad range of clinical and intellectual work being undertaken in the WAP. This journal edition contains a rich array of engaging works – it is dedicated to the memory and works of François Sauvagnat who died in 2020 and features essays poetry / prose and a book review. It begins with several hitherto unpublished papers by Sauvagnat on the topic of ordinary psychosis – I have included some comments in the second part of this introduction to introduce readers to both his contributions to the Lacanian field and his impact on my analytic formation. Next there are two papers on femininity – one a newly translated paper written by Eric Laurent and the other by Astrid Lac. The final essays engage with a range of themes in the Lacanian field: Jane Kent discusses Lacan in relation to anti-philosophy and the act, Jillian Weise writes about Sappho and David Ferraro critically engages with theoretical problems raised by neuropsychoanalysis. The journal also features two poems by Claire Baxter and Michael McAndrew and concludes with Ferraro’s book review of Being, body and discourse: A review of Discourse Ontology: Body and the Construction of a World, from Heidegger through Lacan by Christos Tombrasby.

In memory of François Sauvagnat and some further remarks on ordinary psychosis

François Sauvagnat died on the 15th May 2020. He was professor of psychopathology at the University of Rennes 2, associate research director (Paris 7) and teacher at the Clinical Section of Rennes. He was a clinical psychologist (PhD) and psychoanalyst who had personal clinical and pedagogical dealings with Lacan in the 1970s. His engagement with Lacanian psychoanalysis was extensive and varied over his career. He was a prolific writer publishing articles in books and journals in the Lacanian field, and also in psychiatry and psychology. In addition, he had a particular interest in how Lacan’s training in classical psychiatry informed psychoanalytic theory and practice, and he held interests in the treatment of psychosis and in the structure of hallucinations and elementary phenomena. Sauvagnat’s two papers on ordinary psychosis featured in this volume of PsychoanalysisLacan are the first time they have appeared in print. I would like to extend my thanks and gratitude to the Sauvagnat family for granting permission to print these papers and to Pierre Bonny – a former PhD student of François Sauvagnat and then a colleague at Rennes University – for facilitating permission of the publication process with the Sauvagnat family. Vale François Sauvagnat.

I had the pleasure of corresponding with François Sauvagnat on several occasions over the last decade concerning the topic of ordinary psychosis. The correspondence occurred during the early stages of my PhD research in psychoanalytic studies when embarking on the then emerging field of ordinary psychosis. I initially corresponded with him after reading his paper On the specificity of psychotic elementary phenomena (2000); I found it to be a particularly significant paper as it provided theoretical background on the influence of classical psychiatric concepts on Lacan’s psychoanalytic views on psychosis. Moreover, through reading this paper I could discern its thematic relevance (i.e. latent psychosis; primary and secondary symptoms; elementary phenomena, etc.,) to debates in the field of ordinary psychosis despite the paper predating the emergence of the signifier ‘ordinary psychosis’. The paper also discussed significant psychiatric authors (de Clérambault; Bleuler; Kraepelin; Chaslin) in terms of how they were influential on Lacan’s theorisation of the psychoses. Sauvagnat’s discussion of elementary phenomena outlined how minimal psychotic phenomena might present variably across the psychoses (paranoia, schizophrenia, mania, autism) and he argued for the clinical utility of the elementary phenomena concept in terms of differential diagnosis and the direction of the treatment, especially in cases of diagnostic uncertainly or, where a psychosis was stable and ‘asymptomatic’. And while this paper predated the emergence of debate concerning ordinary psychosis it was clear that the topic of elementary phenomena and classical psychiatric knowledge had important links with the then nascent articulation of ordinary psychosis emerging in WAP throughout the late 1990s.

My correspondence with François Sauvagnat during this time regarding his work and the field of ordinary psychosis was very illuminating and useful. He was kind and generous enough to send me an unpublished manuscript Psychotic elementary phenomena and ordinary psychosis (2009) for comment. This paper and other debates in the field of ordinary psychosis were influential in the development of my own project that integrated the concept of elementary phenomena with body phenomena in psychosis, especially in cases where symptoms were ‘ordinary’ and transitory and provide impetus to theorise the twofold problem of triggering and symptomatisation on psychosis (Redmond, 2014). About a decade later I again had correspondence with François Sauvagnat regarding an edited book on ordinary psychosis that I was co-ordinating. And while the project never came to fruition, he again was generous enough to provide me with a paper – Ordinary psychosis: what it adds to the previous understandings of Lacan’s theory of psychosis (2018). And while I never met Francois Sauvagnat I am most grateful to his memory and acts of generosity and intellectual interest – his willingness to engage with my work across different time spans has made a significant contribution to my academic career, analytic formation and clinical practice.

Ordinary psychosis and the non-orientable neurosis / psychosis distinction

The two unpublished papers – Psychotic elementary phenomena and ordinary psychosis (2009) and Ordinary psychosis: what it adds to the previous understandings of Lacan’s theory of psychosis (2018) provide an interesting insight to his approach to the field. The interested reader will apprehend both the consistency of his views on this topic and the significant number of questions and research possibilities that remain to be developed in the field of ordinary psychosis. The most obvious consistency outlined in the papers in that ordinary psychosis does not constitute a new psychiatric category but remains firmly embedded in Lacan’s concepts of psychosis developed across his entire oeuvre (i.e. the classical 1950’s Lacan and the later Lacan) and, that classical psychiatric discourse must be considered essential in any further development of ordinary psychosis. While the first paper focuses primarily on ordinary psychosis and elementary phenomena the second paper is broader providing commentary on a wide variety of topics in Lacan’s approaches to psychosis that raise more questions than answers. One particular area of interest in the second paper concerns Sauvagnat’s discussion of the neurosis / psychosis distinction in the Lacanian tradition.

A key point Sauvagnat makes here is that the categorical distinction between neurosis / psychosis was probably overstated by Lacanian commentators and that Lacan’s views were quite nuanced over the course of his teachings. On the one hand, this might seem a moot point in light the contemporary clinic of the WAP that has developed the Millerian notion of ordinary psychosis and the ‘later Lacan’ in a manner that clearly overturns the clinical and theoretical utility of categorical diagnostic approaches either implied or developed by Lacan in the 1950’s. On the other, the neurosis / psychosis distinction remains an essential feature of the contemporary clinic and the supposition of a limit point between the two remains valid. An assumption remains that affirms neurosis is a clearly definable clinical structure distinguishable from psychosis (Miller, 2009).

The field of ordinary psychosis emerged from the preservation of the neurosis / psychosis distinction in clinical praxis. Miller’s discussion of ordinary psychosis outlines the necessity of creating an epistemic category in response to the clinical difficulties sometimes encounter when orientated by the neurosis / psychosis distinction. The term “ordinary psychosis” provides an approach to theorising psychosis in a wide variety of presenting cases. Miller remarks:

You say ‘ordinary psychosis’ when you do not recognise evident signs of neurosis, so you are led to say it is a dissimulated psychosis, it is a veiled psychosis. A psychosis that is difficult to recognise as such, but which I infer from various small clues. It’s more of an epistemic category than an objective category. It concerns our way of knowing it (2009, p. 149).

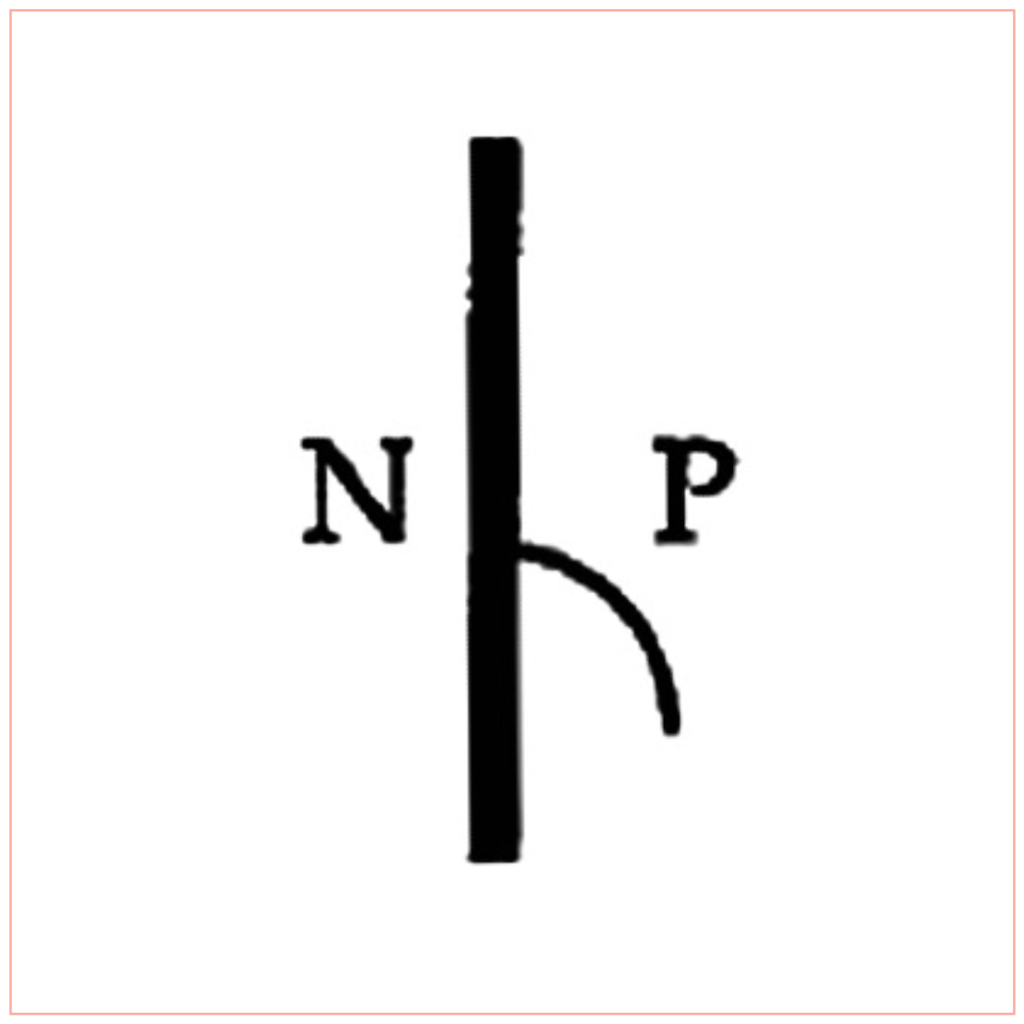

Miller’s (2009) argument is worth noting: if the clinician does not recognise a neurotic structure then they may assume it is a psychotic structure, even if there are no obvious features of psychosis. His claim assumes that neurosis has a definite structure and that clinicians will be able to recognise it. For example, neurosis will be characterised by repetition, the imposition of a limit upon jouissance, evidence of castration and, a clear differentiation between the ego, id, and super-ego (2009); in the absence of these features of neurotic structure, then the analyst may assume he is dealing with a case of psychosis. Thus, one retains the neurosis / psychosis distinction, and by the logic of the “excluded middle”, one is led to conclude psychosis (Figure 1.). In this figure, the bar separating neurosis (N) from psychosis (P) is augmented by the excluded middle, which refers to cases difficult to classify.

Figure 1. The neurosis psychosis distinction and the excluded middle

The logic of the excluded middle refers to instances where clinicians have been unable to make an unequivocal judgement regarding neurosis or psychosis. Miller’s response to this problem is that one should default to psychosis, given that clinicians will recognise neurosis if it is present. Thus, any doubt over the diagnosis entails an assumption of psychosis; it is then incumbent on the analyst to construct a way of knowing the particular presenting case in relation to psychiatric and analytic formulations of psychosis.

The logic of the excluded middle refers to instances where clinicians have been unable to make an unequivocal judgement regarding neurosis or psychosis. Miller’s response to this problem is that one should default to psychosis, given that clinicians will recognise neurosis if it is present. Thus, any doubt over the diagnosis entails an assumption of psychosis; it is then incumbent on the analyst to construct a way of knowing the particular presenting case in relation to psychiatric and analytic formulations of psychosis.

Sauvagnat’s papers on ordinary psychosis engage with the neurosis / psychosis distinction to highlight some possible convergences between the two structures vis-à-vis the fundamental fantasy and elementary phenomena. We can pursue this thread via his discussion of elementary phenomena developed in an earlier paper (1998). He states:

What is at stake in the enquiry about elementary phenomena is to find out what is the implicit structure of the Other, and how the subject tries to calculate his own existence; it is also clear that elementary phenomena are predominantly linguistic phenomena. Two sides can be differentiated:

- Elementary phenomena as questions: this is evidenced by a perplexity, the feeling that one is confronted by an enigma, in a direct confrontation with the foreclosure of the Name-of-the-father.

- Elementary phenomena as attempts to answer to the foreclosure of the Name-of-the-father (‘personal signification’, hallucinations, etc.).

In his account we have the familiar picture of psychotic triggering or destabilisation where perplexity concerning some aspect of the subject’s existence (identity; sexuality; relation to authority; relation to the body, etc) emerges only to be followed (but not always) by a symptomatic response. We can then juxtapose this discussion of elementary phenomena with his comments concerning fantasy in neurosis as he draws attention to the similarity of fantasy to symptomatisation in paranoia and melancholy. He states:

(there is)…the possibility to sort out in non-triggered psychotic cases minimal symptoms which can sum up most of the following delusional developments, in a way quite similar to the ‘fundamental fantasy’ in the neurotic cases (pg. 6);

There is a similarity between the function of psychotic delusion and that of the neurotic fantasy (pg. 6); and,

A type of knotting in which the equivalent of the fundamental fantasy is in force, as in paranoia or melancholia (pg.14).

These statements are interesting for several reasons. First, it may imply that the fundamental fantasy in neurosis is a kind of limit point separating it from psychosis and the fundamental fantasy is similar or even equivalent to certain kinds of knotting in paranoia and melancholia. One response to these provocations may be to consider some features between fundamental fantasy and elementary phenomena which are as follows:

- Elementary phenomena involve a relation of the subject with the Other concerning some questions of existence (i.e. identity, sexuality, authority);

- The structure of fantasy, written $<>a, posits the barred subject in relation to the object.

On the one hand, elementary phenomena show that the subject is responding to the enigmatic desire of the Other whereas in the fundamental fantasy the subject is articulated in a relation to the object. Should we assume that there is an absence of the fundamental fantasy in psychosis and that its presence is a pathognomonic feature of neurosis? Another consideration is the function of fantasy in neurosis; as we know, in both Freud and Lacan it is considered a mode of defence; in neurosis, fantasy presents an articulated response to the Other (Che voi?), or rather, the subject remains in a fixated position in terms of what the Other wants from them, which has implications in terms of both jouissance and desire. In this sense the fundamental fantasy, while harbouring a relation with the object, is also organised by the subject’s relation to the Other. We could suppose that the libidinal destabilisation often encountered in psychosis might be due, in part, to the absence of the neurotic mode of defensive function that is obtained via the fundamental fantasy. The question of what kind of fantasy structure operates in psychosis is an important question; Lacan’s remark that the “psychotic subject carries the object in his pocket” indicates that the structure of fantasy in psychosis is not equivalent to the neurotic subject.

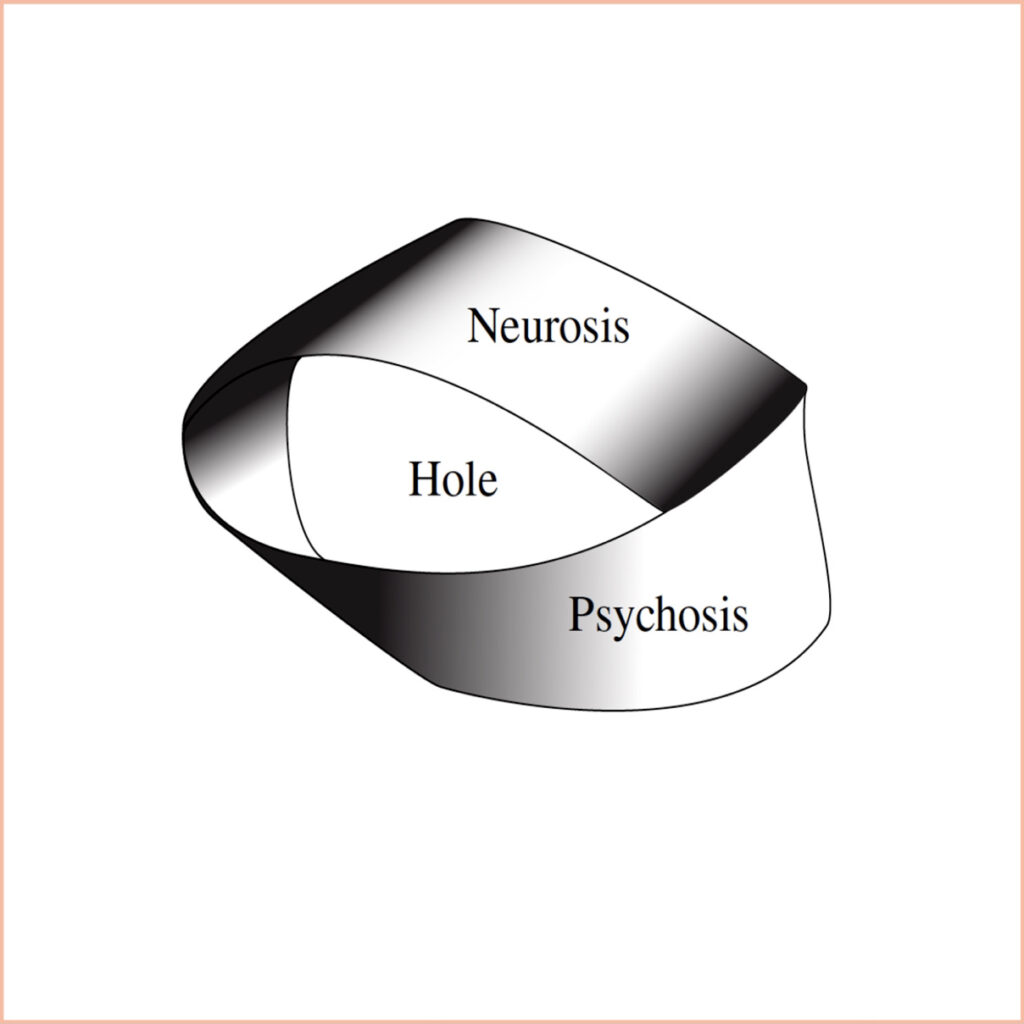

Returning to Sauvagnat’s assertions concerning the equivalence between elementary phenomena and fantasy we might conjecture that the symptomatisation at work in elementary phenomena is an attempt to create a structure with the equivalent defensive function of the fundamental fantasy. This proposition requires further elaboration and development that goes beyond this paper. However, we can make a few statements that orientate this inquiry. First, the proximity between neurosis and psychosis is quite subtle; of course, in Lacan’s later teachings, we have the assertions made by Lacan that “we are all mad” and that “madness is no longer a privilege”; moreover, Miller has provided coordinates to develop these aphorisms with his focus on delusion, dupery and mental debility. Another way to consider the neurosis / psychosis distinction with reference to the fundamental fantasy and elementary phenomena is via the concept of the vanishing mediator. As seen in Figure 2., the neurosis / psychosis distinction can be shown on the non-orientable topological object known as the Möbius strip.

Figure 2. The neurosis / psychosis distinction and the vanishing mediator

This figure allows several pedagogical advantages. First, it allows us to represent the neurosis / psychosis distinction around the hole, the hole harbouring a real that is universal yet contingent for all speaking beings (i.e. the defence against the real). Second, the non-orientable quality of the Möbius strip provides a useful heuristic device for assessing the status of the neurosis / psychosis distinction in the field of ordinary psychosis. The Möbius strip is a non-orientable mathematical object – an object with a one-sided surface with no boundary when represented in 3-dimensional Euclidean space. A strip of paper with two sides serves as the model: on one side of the paper is written ‘neurosis’ and on the other side ‘psychosis’. To make a Möbius strip the paper is then twisted and joined together to make a band creating a hole. The neurosis / psychosis distinction when written on the Möbius strip shows how the transition between neurosis and psychosis has an undecidable continuity. Paradoxically, the distinction between the neurosis and psychosis is made via two sides of the paper but the twist and join that is made to create the Möbius strip loop and hole transforms the distinction from one of mutual exclusion to that of continuity where a clear limit separating the two becomes impossible to localise. Moreover, we might postulate that the localisation of this limit can be theorised with reference to elementary phenomena and the fundamental fantasy via the Hegelian notion of the ‘vanishing mediator’ – that is to say, we might assume that the vanishing mediator between neurosis and psychosis concerns the strange transformation between the neurotic fundamental fantasy and psychotic experience of elementary phenomena. Fleshing out this limit point of vanishing mediation between neurosis and psychosis may provide a fruitful line of research in the spirit of Sauvagnat’s remarks concerning the strange proximity between the two clinical structures.

References

Redmond, J. (2014). Ordinary psychosis and the body: a contemporary Lacanian perspective. Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK.

Sauvagnat, F. (2000). On the specificity of psychotic elementary phenomena. Psychoanalytic Notebooks of the European School of Psychoanalysis, 1, 95-110.